Born during the last few years of the Second World War, Werner Herzog would become one of the central pillars of the New German Cinema movement that took place from the early 1960’s until the 1980’s. His unique approach towards filmmaking would see the director constantly seek out strange and interesting characters, through whom he would tell bizarre stories.

Following on from film-makers such as Tod Browning, Herzog created films based around marginalized characters such as dwarfs, deaf-mutes, obsessive Spanish explorers and even the vampire Nosferatu. His work would go on to influence a whole new generation of filmmakers from Harmony Korine to Christopher Nolan. He would be ranked as one of the most influential filmmakers of all time.

To date, Werner Herzog has directed 68 films, most of which have been documentary feature films. The majority of his feature films were made in the 1970’s and 80’s. After the notoriety his early short films gained him, he was able to make his breakthrough feature film Aguirre, Wrath of God in 1972, which starred Klaus Kinski.

Since gaining international critical acclaim Herzog has only made a few short films, all of which have been documentaries. Like most directors, he began by making short feature films. In-between 1962 and 1968, he was able to make 5 short films that have largely become overshadowed by his later feature films. These early works deserve more recognition for their originality and as being interesting documents that give an insight into a raw and unrefined Herzog.

Read Aslo

- 10 Best Short Film Blogs

- The Best 10 Short Film Festivals

- Is It Worth Making Your Short Film Without the Right Budget?

Made in 1966, The Unprecedented Defense of the Fortress Deutschkreutz is arguably the best Herzog short film as it contains all the hallmarks of the style for which the director would later become known. It was Herzog’s 3rd short film and his first to deal with a subject matter that related to The Second World War. The war was a massive influence on all the young directors of the New German Cinema movement, and Herzog would be no different. In later interviews and in his writings he would refer this event as having a major influence on his childhood and view of the world.

The film’s plot revolves around four young men who are seen to break into an old castle that was once a major battleground between German and Russian forces during World War 2. Once inside, they discover some abandoned army uniforms and equipment that includes weapons. Things begin to take a strange direction when the four men decide that they must defend the castle against an army of imagined attackers at all costs.

Herzog uses a number of plot devices to create a surreal dreamlike world where the audience is made to feel unsure of the onscreen action. It forces them to question whether this a kind of mass illusion of some kind? Is it just that these men are all disturbed? Are the events meant to be interpreted literally?

The Unprecedented Defense of the Fortress Deutschkreutz is shot in black and white and features no dialogue, but rather a single narrator who recounts stories that are often unrelated to the events onscreen. One such example occurs as the men are readying themselves for battle by marching back and forth. The narrator begins: “a week with nine days has proven itself to be best because nine is more easily divided by five than seven is”. This bizarre overdub is totally unrelated to the events happening onscreen and so serves to unnerve the viewer by making these events seem more ambiguous and unexplainable.

This simple technique illustrates much of Herzog’s style, where strange plots are driven by unexplainable character behavior. This forces the viewer out of their normal ‘passive’ viewing into a place where they are asked to question what they are seeing in order to find out the answers for themselves.

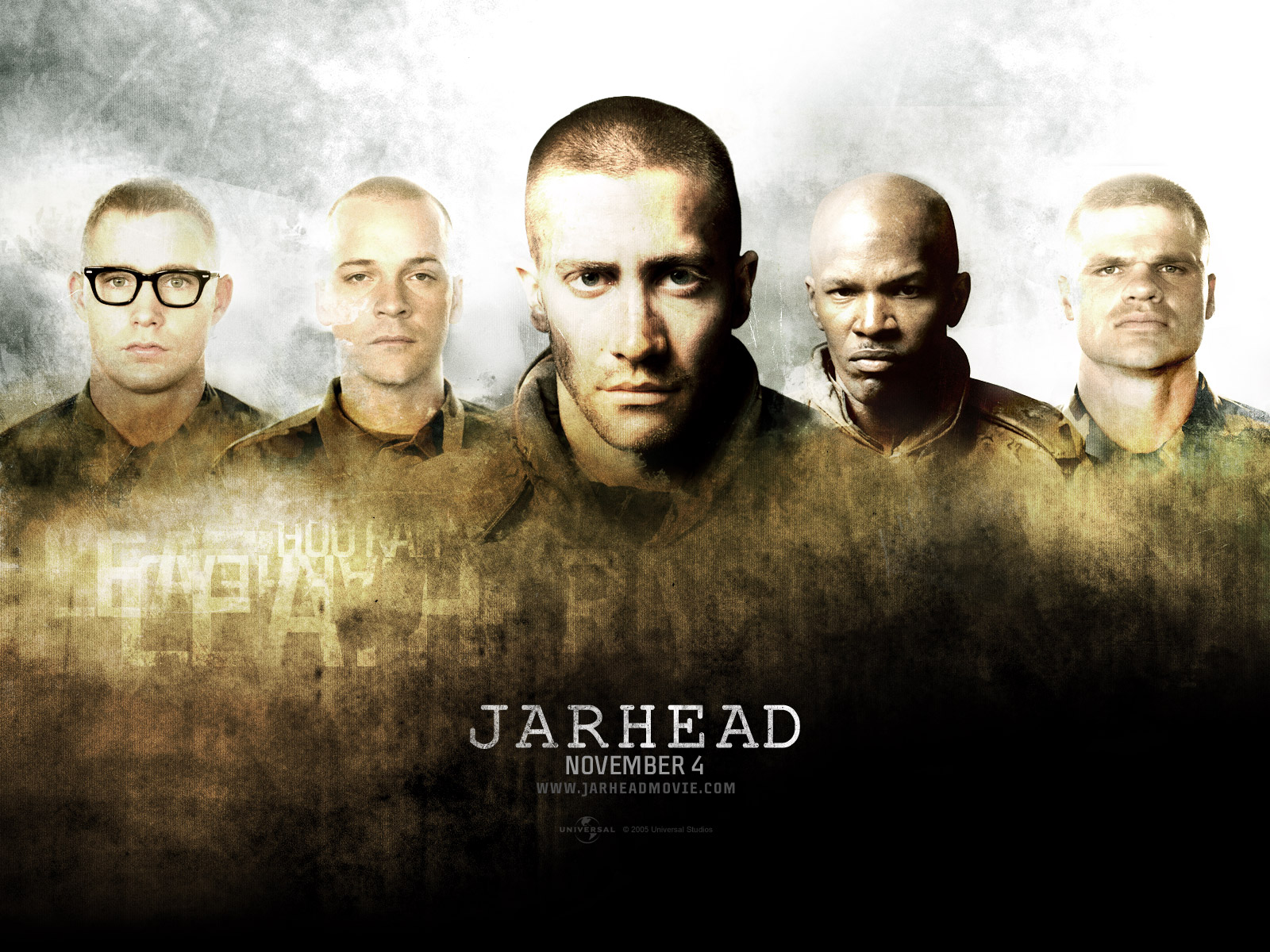

As the film progresses the four men begin to become disheartened by their imagined enemy’s lack of action. We see how the pressure of waiting under such tension causes one of the men to mentally break down, whereupon he has to be forcibly restrained by the others. Rejecting the conventional norm of movies to focus on the ‘action’ of war, the film instead shows how the build-up to war is a trauma in itself. This theme was something that would not be thoroughly explored by Hollywood until many decades later in the movie Jarheads, showing just how visionary this film was for the time.

Read Also

- What Data Can Be Used To Make Better Movies

- How Understanding Your Audience Will Make Your Independent Movie a Success

- 10 Best Jack Nicholson Movies

Herzog has described The Unprecedented Defense of the Fortress Deutschkreutz as “a satire on the state of war and peace and the absurdities it inspires.” It is, however, also an insightful look at the human psyche and our fundamental need for conflict to somehow define ourselves. The film suggests that even in the absence of conflict, our overwhelming desire to seek it out wherever we can, even if it must be in our imagination, defines us as human beings.

Despite the simplicity of the sets and wardrobe, Herzog brilliantly manages to create a surreal feeling to the events unfolding onscreen. Without question, this film is a great example of an unrefined Herzog that gives a clear insight into how he would later go on to use innovation and unusual character behavior as a central plot device.

In the case of The Unprecedented Defence of the Fortress Deutschkreutz, Herzog’s greatest innovation is the technique that allows the viewer to gaze in from the outside in rather than viewing the events from the point of view of the soldiers. This subverts the normal audience/character relationship that is the backbone of mainstream film and offers the audience a new way of seeing the absurdity of war.

Stay connected